The #SPWM21 Inaugural Translation Week: An After-Action Report

Ho Zhi Hui writes an after-action report for SPWM 2021’s inaugural Translation Week.

/ Article by Ho Zhi Hui

In 1991, the Japanese police were called to Tsukuba University, northeast of Tokyo. A cleaning lady had come in to do her rounds and discovered the body of Hitoshi Igarashi, an assistant professor of comparative Islamic culture: he had been knifed in the neck and slashed across the face. Till today, his murder remains unsolved, but my translation theories professor delights in telling this macabre story to all his classes.

Igarashi was the Japanese translator for Salman Rushdie’s infamous novel, The Satanic Verses.

*

Thankfully, there have been exactly zero (0) murders as a result of this year’s inaugural Translation Week, though there may well have been people who felt like murdering me.

When I first started thinking of prompts for this year’s SPWM, I was nervous. I didn’t know what the public response would be: I wanted our participants to experience the difficulties that any serious translator would experience, but I also wanted it to be fun and interesting. At the same time, I wanted translation week to be multilingual, but that meant machine translation – and I worried that inaccuracies or misunderstandings would wound the collaborating poets who so kindly offered up their work as source texts.

I took a crack at poems myself, running them through Google Translate and other engines such as Youdao or Glosbe to see what the (sometimes tragic, sometimes hilarious) results were. The poets and writers of Young Writers Circle, 所谓诗社 (matter.less), Main Tulis and Mr Samsudin Said not only contributed the source texts, but also generously helped me to interpret and provide a glossary of important terms, with resources to help our participants.

In the end, though, I needn’t have worried – the poets of SPWM rose to the occasion and produced work that just blew me away.

*

The trap begins at the title:《追问》 by @containfalls variously became “Inquiry”, “Unasked”, “to be present”, “Jasmine”, “Your Love is Your Jasmine Garden”, “Interrogation”, “lost”, and “to the heart of the matter”. And correspondingly, poets produced poems that varied drastically in tone from Lim Yi Jie’s determined “I’m still in that dry damn desert / still not backing down”, to the regretful lines of Gan See Siong’s “I am an arrogant fool, flapping like a flag”. Kalpana Mani wrote a tender third-person translation, in which “the gardener escapes” to his “sanctuary”, and Laura Therese Tan produced a plaintive, murmuring poem: “I grow no roots / in the spongy soil of your love.”

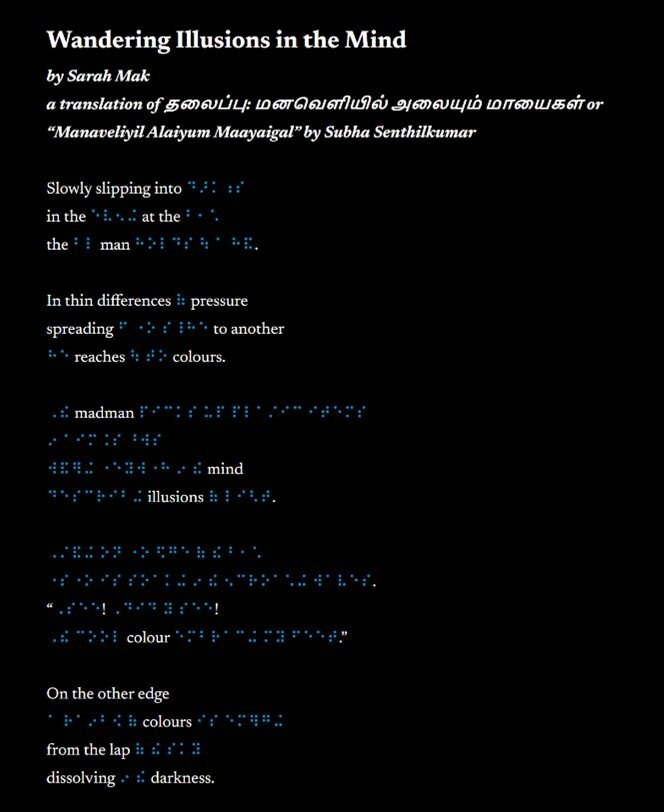

There were also exquisite experiments with form: Sarah Mak produced an interactive translation of தலைப்பு: மனவெளியில் அலையும் மாயைகள் (“Manaveliyil Alaiyum Maayaigal”) by Subha Senthilkumar that I spent many delighted minutes clicking through.

Janice Heng transcreated a scene from the play “Kerana Nila”, by Adib Kosnan, using the text from the machine translation but whiting out parts and altering names.

The sheer range of work demonstrates that every translator is a reader first and foremost. Translation makes the work of reading visible: if we really engage with a text, we chew it over, we consider how it makes us feel and we think deeply about what it means to us.

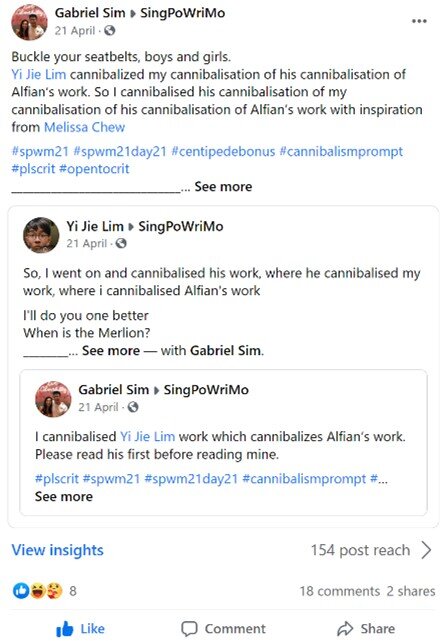

Writers sometimes took “chewing things over” quite literally. The prompt for Day 21 was “The Cannibalism Prompt” – it followed the work of Brazilian postcolonialist writers and thinkers, who advocated eating the old dominant texts, digesting them, and using them to nourish your own creative practice. Among the responses was a gigantic daisy chain of works regarding the Merlion, all of which explored the significance of that iconic monument and our love-hate relationship with it. Many of the poems also referenced earlier works by poets such as Alfian Sa’at and Edwin Thumboo, exploring not only the translation of language but the transformation of meaning.

Finally, poets had a go at translating their own work (Day 20: Singaporeans are bilingual, right? Well, prove it.). The Bilingualism Prompt grew out of my own insecurities – I’m a jiak kentang, a banana, and as a teenager I was more at ease with Milton than Yeng Pway Ngon, more able to recite the lists of Roman emperors than those of the Chinese dynasties. Even now, as a professional translator, I think of Chinese as my “B language”, the one that I am less fluent in.

I think my situation is representative of many of the English poets and creatives who write primarily in English, and indeed, many people greeted the prompt with howls of dismay. But I think that there is immense value in re-thinking your own thoughts in another language, trying to express the same message with different techniques, in a language that you may feel is less under your power. The attempt produced gems such as Rodrigo Dela Peña Jr.’s amazing emoji poem, the immensely detailed QUEUE / 队列 / BERATUR / வரிசை by Al Hafiz Sanusi, and the square, sparse form of Valen Lim’s House (Moving), among many others.

*

When I was discussing this article with the editors, one of them said, “Oh, I’ve always heard translation is dead.” ;________;

Translators are, indeed, always nervous about our place in the literary ecosystem. There is no shortage of criticism for us: we are sometimes called traitors and sometimes called slaves (occasionally simultaneously, as in the case of La Malinche). But translators today are pushing forward and trying to show the reading public a more diverse range of works, and transcreators are increasingly exercising their own creative muscle. That’s what this year’s Translation Week attempted to achieve – and I think we managed a good start.